Technology in (Mathematics) Education: A Cautionary Tale

Over my years in education, I’ve come to realize that there are many competing views of the nature of learning. Wildly different views of that glorious capacity of humans to be more and know more and do more than we could in the past. I’ve even had a few of those different views. But recently at the 2015 NCSM Annual Conference, Dan Meyer provided me one I hadn’t really considered fully. Dan’s talk was titled The Future of Math Textbooks (if Math Textbooks have a Future) and while the talk was both interesting and informative, I fixated on a single example he gave to spur thought. It came in the form of a picture that lodged in my mind and created a scenario. Let me paint that picture for you:

Your child goes to school every day to a building not unlike those of that exist now. But this school is different. The classrooms that normally would have been filled with laughing children surrounded by a riotous blend of colors and sights are gone. Instead, this school is filled with rooms and rooms of small cubicles, each with a single computer screen staring blankly out of it. Yes, this school is different. Teachers have been replaced with “lab monitors” because the wealth and knowledge of the world is stored in the technology behind the pixilated, liquid crystal glory that is the computer screen. Your child sits at one of these screens and the computer becomes the source of all of his or her learning. Sights and sounds fly from the computer, engaging your child in activities and interactions beyond count, expanding knowledge, delivering facts. This deluge of information and experience is also personalized, because the computer can gauge your child’s understanding and interests as he or she learns. Infinite personalization and infinite differentiation in one small, silicon-based package.

Sounds great, doesn’t it? This vision is appealing for many reasons: technology is cheaper, more efficient; the computer is essentially an infinitely patient tutor; the computer can provide a personalized educational experience for every child; the computer can integrate media in multiple ways through multiple sources and display them for students simultaneously. These are but a few of the affordances of technology. It is a tempting thing, this holy grail of education, sitting there on its pedestal all shiny and new. We should embrace this next generation of education, this alternative view. Shouldn’t we?

I think not.

The vision laid out above haunts my nightmares. It terrifies me beyond belief.

I’m terrified because this vision of education ignores an aspect of learning that I’ve come to believe is fundamental to both schooling and learning a subject like mathematics. The reality is that learning mathematics is a social activity, with many nuances and variations, but not something that can be done alone as well as it is done in the company of and in collaboration with others. In fact, some of the greatest minds in education would say that schooling in general is a social activity. Certainly someone like Dewey would agree with this idea.

The idea that school is about more than just learning content is certainly not new, but it tends to get overlooked in the rush to adopt and implement technology in today’s schools. It is enough that kids get recess and gym class and specials and field trips, technology advocates say. But it isn’t. Technology is undeniably transformative when used appropriately. However, the presence of technology is not enough. Many school systems today, in their rush to be seen as cutting-edge, adopt a “if we provide it, they will use it” mentality. This perhaps unconscious nod to the otherworldly advice from Field of Dreams unfortunately doesn’t translate from the silver screen to the computer or tablet screen. Providing the technology to teachers and students, while necessary, is never sufficient. But I digress.

The more insidious problem with technology is that, currently at least, the technology for a fully integrated, social learning environment involving spatially (or even temporally) separated participants does not exist. Nothing exists that mimics the learning that takes place in a student-centered classroom if the learners are not present in the same room. There are some great math education minds thinking about these things. Jere Confrey, Phil Daro, Chad Dorssey, and AJ Edson are just a few. Confrey and Daro are working with commercial publishing companies to design high quality digital curricula, and Confrey in particular is thinking about truly digital learning environments. However, even these people are basing their visions on a student-centered, social learning model. A great deal of research supports this position, particularly that of Paul Cobb on social constructivism in the 1990’s. The idea of situated learning consistent with socially constructed knowledge and knowing posited by Jean Lave and Ettiene Wenger in 1991 is another prime example. While Cobb’s work focused in mathematics, Lave and Wenger’s work is much more general. With the extensive research base that supports socially constructed knowledge, reality, and meaning, it is hard to see how technology can effectively deliver that kind of learning independent of a collaborative, social environment.

Some may read my statements so far as those of someone generally opposed to technology in schools. Nothing could be further from the truth. Additionally, I am not a person to throw out criticisms or advocate against a particular approach in a vacuum. I believe that those that see a problem with a system have an obligation to, in addition to providing constructive criticism, provide an alternative path or a remedy to the identified problems.

In the interest of the aforementioned obligation, I have several thoughts for readers to consider. First, technology is and should be a vital means by which students can learn more mathematics, more deeply than ever before. My argument is not an existence objection, but an application one. The benefits of technology in the classroom are extensive, when it is used properly.

Thought 1: Technology increases access for all students, and struggling students in particular.

It increases access through at least two paths: multiple representations (mathematical and technological) and earlier access to concepts within the instructional stream. These two paths are not distinct; in fact, they are indivisibly intertwined. Consider an example from high school mathematics:

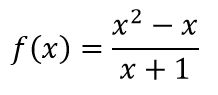

Identify and describe the key features of the following function:

Your child goes to school every day to a building not unlike those of that exist now. But this school is different. The classrooms that normally would have been filled with laughing children surrounded by a riotous blend of colors and sights are gone. Instead, this school is filled with rooms and rooms of small cubicles, each with a single computer screen staring blankly out of it. Yes, this school is different. Teachers have been replaced with “lab monitors” because the wealth and knowledge of the world is stored in the technology behind the pixilated, liquid crystal glory that is the computer screen. Your child sits at one of these screens and the computer becomes the source of all of his or her learning. Sights and sounds fly from the computer, engaging your child in activities and interactions beyond count, expanding knowledge, delivering facts. This deluge of information and experience is also personalized, because the computer can gauge your child’s understanding and interests as he or she learns. Infinite personalization and infinite differentiation in one small, silicon-based package.

Sounds great, doesn’t it? This vision is appealing for many reasons: technology is cheaper, more efficient; the computer is essentially an infinitely patient tutor; the computer can provide a personalized educational experience for every child; the computer can integrate media in multiple ways through multiple sources and display them for students simultaneously. These are but a few of the affordances of technology. It is a tempting thing, this holy grail of education, sitting there on its pedestal all shiny and new. We should embrace this next generation of education, this alternative view. Shouldn’t we?

I think not.

The vision laid out above haunts my nightmares. It terrifies me beyond belief.

I’m terrified because this vision of education ignores an aspect of learning that I’ve come to believe is fundamental to both schooling and learning a subject like mathematics. The reality is that learning mathematics is a social activity, with many nuances and variations, but not something that can be done alone as well as it is done in the company of and in collaboration with others. In fact, some of the greatest minds in education would say that schooling in general is a social activity. Certainly someone like Dewey would agree with this idea.

The idea that school is about more than just learning content is certainly not new, but it tends to get overlooked in the rush to adopt and implement technology in today’s schools. It is enough that kids get recess and gym class and specials and field trips, technology advocates say. But it isn’t. Technology is undeniably transformative when used appropriately. However, the presence of technology is not enough. Many school systems today, in their rush to be seen as cutting-edge, adopt a “if we provide it, they will use it” mentality. This perhaps unconscious nod to the otherworldly advice from Field of Dreams unfortunately doesn’t translate from the silver screen to the computer or tablet screen. Providing the technology to teachers and students, while necessary, is never sufficient. But I digress.

The more insidious problem with technology is that, currently at least, the technology for a fully integrated, social learning environment involving spatially (or even temporally) separated participants does not exist. Nothing exists that mimics the learning that takes place in a student-centered classroom if the learners are not present in the same room. There are some great math education minds thinking about these things. Jere Confrey, Phil Daro, Chad Dorssey, and AJ Edson are just a few. Confrey and Daro are working with commercial publishing companies to design high quality digital curricula, and Confrey in particular is thinking about truly digital learning environments. However, even these people are basing their visions on a student-centered, social learning model. A great deal of research supports this position, particularly that of Paul Cobb on social constructivism in the 1990’s. The idea of situated learning consistent with socially constructed knowledge and knowing posited by Jean Lave and Ettiene Wenger in 1991 is another prime example. While Cobb’s work focused in mathematics, Lave and Wenger’s work is much more general. With the extensive research base that supports socially constructed knowledge, reality, and meaning, it is hard to see how technology can effectively deliver that kind of learning independent of a collaborative, social environment.

Some may read my statements so far as those of someone generally opposed to technology in schools. Nothing could be further from the truth. Additionally, I am not a person to throw out criticisms or advocate against a particular approach in a vacuum. I believe that those that see a problem with a system have an obligation to, in addition to providing constructive criticism, provide an alternative path or a remedy to the identified problems.

In the interest of the aforementioned obligation, I have several thoughts for readers to consider. First, technology is and should be a vital means by which students can learn more mathematics, more deeply than ever before. My argument is not an existence objection, but an application one. The benefits of technology in the classroom are extensive, when it is used properly.

Thought 1: Technology increases access for all students, and struggling students in particular.

It increases access through at least two paths: multiple representations (mathematical and technological) and earlier access to concepts within the instructional stream. These two paths are not distinct; in fact, they are indivisibly intertwined. Consider an example from high school mathematics:

Identify and describe the key features of the following function:

Now, I realize that this is not exactly an enticing mathematical context for students. However, it is one that would appear in the majority of traditional advanced algebra or pre-calculus courses. The mathematical goals behind this task might be as follows:

1. Students will understand the possible key features of a rational function.

2. Students will identify key features of rational functions in examples.

3. Students will explain how key features of a rational function relate to different representations of that function.

4. Students will understand algebraic techniques for determining key features of rational functions.

I wrote these four goals in descending order of importance, according to my beliefs. Other orders are possible (indeed likely), depending on particular views of mathematics. Let’s examine how an instructional plan for this function might look. But wait, I’m going to curtail you. I need you to make two plans: one assuming you have technology, and one assuming you don’t. Pay particular attention to when the major concept of “key features of rational functions” appears in your trajectory for students.

[Devise your plans before moving on. Don’t worry about detail, just give a flow of ideas/skills.]

Here is how my plans look.

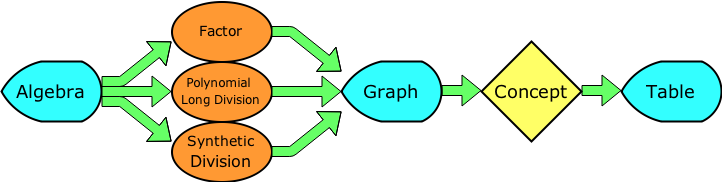

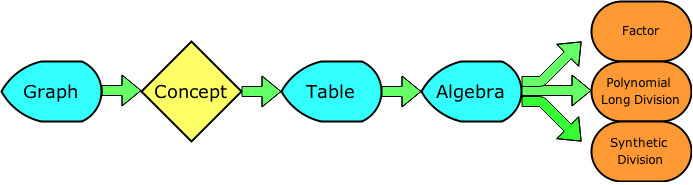

Without Technology

With Technology

Notice the difference? Concept appears so much earlier in the sequence when technology is present, not to mention the fact that it is so much more efficient to use technology to produce representations. This allows students to see many more examples in the timeframe of perhaps one or two examples in settings without technology. In the presence of technology (effectively used) the idea of representational fluency (Kieran, 2007), always central in algebra courses, now becomes much more accessible to many more students. Here I’m reminded of a quote on Twitter attributed to Jo Boaler that goes something like “If there are more ways to be successful, then more students will be successful.”

Technology allows and facilitates student success through both efficiency in creating multiple representations and through its ability to display dynamic, multimedia content. Videos, blogs, songs, clickable, drag-able entities, animations, programmable applications—the options are almost limitless. And none require that kids sit in rows of cubicles. However, these things do not come naturally to either teachers or students and so another thing is needed.

Thought 2: Any technology infused into a classroom should come with both a plan and the appropriate training for all stakeholders.

Remember my Field of Dreams reference? Well here is the remedy. Plan. It’s as simple as that. But I don’t mean plan as in “Run the numbers. Can we afford this? How many will we need?” No, I mean plan as in “What do we want technology to do for us? What does research say is the most effective use of technology in the classroom? Who should have it? How much should they have? Should we phase in or flood? How will we ensure that this tech is used? What training is needed? What lessons have other schools learned?” These are just a few of the questions, in addition to the cost questions, that should be answered thoroughly in any instructional technology initiative.

For mathematics education in particular, NCSM (National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics) has authored a white-paper with CoSN (Consortium for School Networking): Mathematics Education in the Digital Age. This paper would make a wonderful starting point for talking about the questions I asked above.

Another interesting thought about planning for technology implementation is the idea that personal use and classroom use are two very different things for both teachers and students. This idea was brought home to me by a presentation at a CSMC conference in which a teacher talked about how the district had carefully planned for the introduction of iPads into their district. They made the devices available to the teachers for a year before they gave them to students in the hope that teachers would have time to “get used” to the new tech before students got it. This seemed like a good plan until the next year when school officials realized that some teachers (but not all) had gotten used to the technology, but for using it in their personal lives not their classroom instruction. Teachers could check their emails and could go to websites, but really had no idea how to use the technology to instruct. This disconnect, for them, underscored the need to plan better. To take a different view of technology implementation.

A Final Thought: Haste makes waste.

Yes, I know I just resorted to cliché. However, in this case it is the literal truth. When it comes to technology in the classroom, nothing is a greater waste than to have staff and students doing nothing but checking email and surfing social media on the new technology provided by the school.

So don’t be in a hurry for the mechanized, pixilated vision from the beginning of this entry. Not only is it too early for such a thing to truly be possible, but I don’t believe that it will ever be preferable. Beware of that oft-touted holy grail: Personalized Education—it’s a dangerous myth. If you are going to implement technology in your classroom or in your district, make sure you plan first. Plan well. Plan much. And above all, ask questions. Know the research, ask the experts, ask those who have gone before you.

Technology has great potential, but like any tool it must be used wisely. How wisely are you prepared to use it?

References

Cobb, P., Yackel, E., & Wood, T. (1992). A constructivist alternative to the representational view of mind in mathematics education. Journal for Research in Mathematics education, 2-33.

Kieran, C. (2007). Learning and Teaching Algebra. Second handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning: A project of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 1, 707.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge university press.

Technology allows and facilitates student success through both efficiency in creating multiple representations and through its ability to display dynamic, multimedia content. Videos, blogs, songs, clickable, drag-able entities, animations, programmable applications—the options are almost limitless. And none require that kids sit in rows of cubicles. However, these things do not come naturally to either teachers or students and so another thing is needed.

Thought 2: Any technology infused into a classroom should come with both a plan and the appropriate training for all stakeholders.

Remember my Field of Dreams reference? Well here is the remedy. Plan. It’s as simple as that. But I don’t mean plan as in “Run the numbers. Can we afford this? How many will we need?” No, I mean plan as in “What do we want technology to do for us? What does research say is the most effective use of technology in the classroom? Who should have it? How much should they have? Should we phase in or flood? How will we ensure that this tech is used? What training is needed? What lessons have other schools learned?” These are just a few of the questions, in addition to the cost questions, that should be answered thoroughly in any instructional technology initiative.

For mathematics education in particular, NCSM (National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics) has authored a white-paper with CoSN (Consortium for School Networking): Mathematics Education in the Digital Age. This paper would make a wonderful starting point for talking about the questions I asked above.

Another interesting thought about planning for technology implementation is the idea that personal use and classroom use are two very different things for both teachers and students. This idea was brought home to me by a presentation at a CSMC conference in which a teacher talked about how the district had carefully planned for the introduction of iPads into their district. They made the devices available to the teachers for a year before they gave them to students in the hope that teachers would have time to “get used” to the new tech before students got it. This seemed like a good plan until the next year when school officials realized that some teachers (but not all) had gotten used to the technology, but for using it in their personal lives not their classroom instruction. Teachers could check their emails and could go to websites, but really had no idea how to use the technology to instruct. This disconnect, for them, underscored the need to plan better. To take a different view of technology implementation.

A Final Thought: Haste makes waste.

Yes, I know I just resorted to cliché. However, in this case it is the literal truth. When it comes to technology in the classroom, nothing is a greater waste than to have staff and students doing nothing but checking email and surfing social media on the new technology provided by the school.

So don’t be in a hurry for the mechanized, pixilated vision from the beginning of this entry. Not only is it too early for such a thing to truly be possible, but I don’t believe that it will ever be preferable. Beware of that oft-touted holy grail: Personalized Education—it’s a dangerous myth. If you are going to implement technology in your classroom or in your district, make sure you plan first. Plan well. Plan much. And above all, ask questions. Know the research, ask the experts, ask those who have gone before you.

Technology has great potential, but like any tool it must be used wisely. How wisely are you prepared to use it?

References

Cobb, P., Yackel, E., & Wood, T. (1992). A constructivist alternative to the representational view of mind in mathematics education. Journal for Research in Mathematics education, 2-33.

Kieran, C. (2007). Learning and Teaching Algebra. Second handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning: A project of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 1, 707.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge university press.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed